In June of 2020, I was back in New York City. Fatal Covid cases were alarmingly high. There was no vaccine. Many people were wary to venture outside. Others already tired of restrictions were flouting safety recommendations. The unseasonably high temperatures, like walking through cement humidity, navigating crowded sidewalks–donning the recommended facemask which felt more asphyxiating than protective–was not fun. And seeing loved ones was tricky.

It was also Culture Shock. I’d just come from daily hikes in Patagonia, enjoying country air and stunning vast vistas. The only living beings I’d likely encounter had four legs or wings.

I knew my trials paled to so many, but I also knew I didn’t want to stay in NYC.

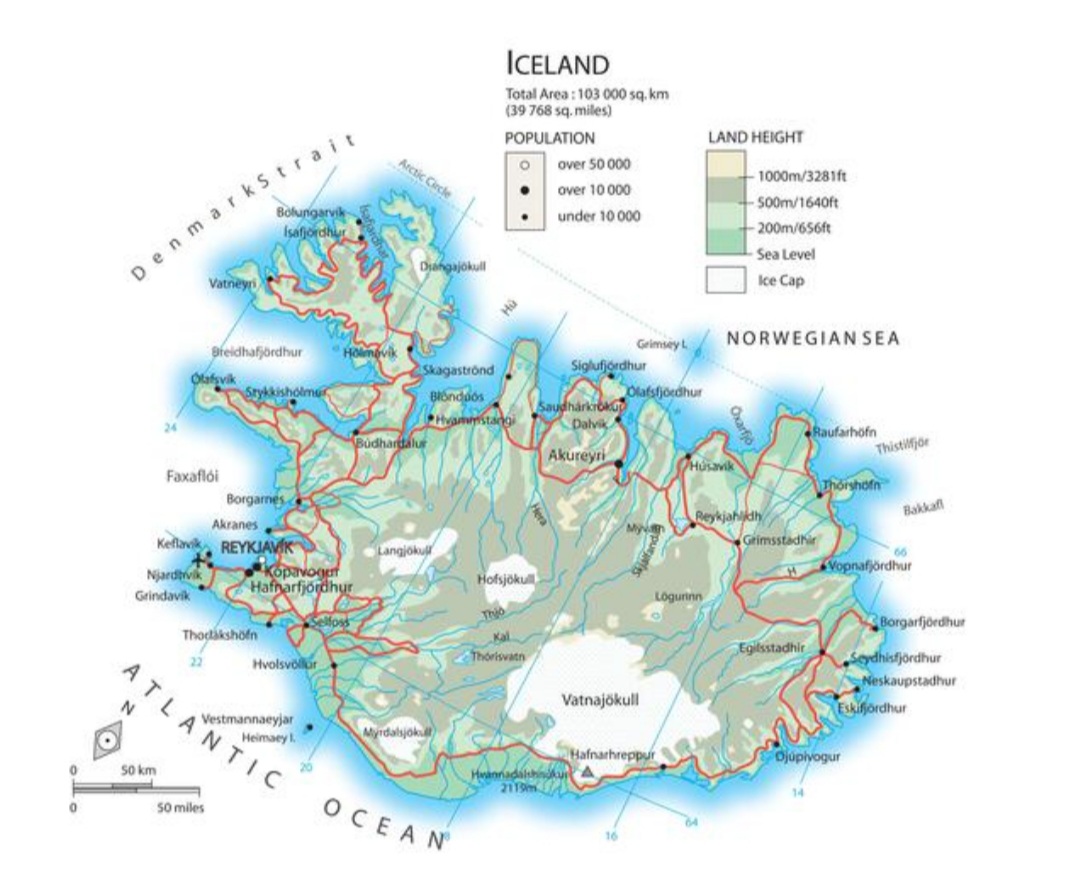

I happened upon an article showcasing Iceland as the poster child of the pandemic: cases were low and isolated. I’d thought of going in the past, but always ended up elsewhere. It seemed like now was the perfect time. Although Americans (and Chinese–Iceland’s top non-European tourist groups) were denied entry, I’d be able to enter with my French passport. Direct flights from NY were canceled, but a flight via Amsterdam was available.

Although the transatlantic flight had few passengers, the Amsterdam to Reykjavik flight was packed. The unoccupied middle-seat policy had been lifted. The very tall Frank and petite Ellen from Holland sat next to me and we were soon speaking of travel. Our eyes conveyed what our masked faces could not. They were renting a van for three weeks to travel Iceland’s popular Ring Road. We exchanged numbers and hoped to see each other again.

Upon entry, two Covid tests(swabs in both nose and throat) were administered by a good-natured staff wearing the requisite protective pandemic attire. Arriving passengers were expected to isolate until we received our results. But there was no restriction leaving the airport on a public bus. Gazing upon Iceland for the first time, I was markedly underwhelmed. The bus window framed a flat, shrubby landscape, and indistinct home developments. “Beautiful” did not come to mind, but a joke I’d been told did, “If you get lost in a forest in Iceland, just stand up.”

The apartment I’d rented in downtown Reykjavik was spacious with large windows, but only a few small panes actually opened. When the wind came through I understood why. The furnishings were understated and lovely.

Iceland seemed both foreign and familiar.

When I ventured out for some groceries I passed two-story attached, beige buildings, similar to the one I was staying in. They led to smaller private homes and yards on quiet streets. There was little traffic and few people. I complemented a woman on the garden she was tending bursting with flowers and greenery. She seemed pleased. A nearby corner shop, with just enough space to do a jumping jack, had two coolers, a counter, and shelves all packed with goods: dried fish and meats, dairy products, beverages, and many items I did not recognize. I gravitated toward the most recognizable and the shop owner did his best to explain some others. Feeling more jet-lagged than adventurous, I left with fresh brown bread, cucumbers, tomatoes, fresh cheese, coffee, and skyr (think yogurt).

The small and appealing coastal city, easily navigable on foot, offered plenty to see including historic wooden homes, stone structures, bold modern architecture, a pretty port, duck pond, beach, lovely lanes, restaurants, cafes, and the Phallological Museum which boasts a collection of all the mammal phallic specimens in Iceland. I somehow never got there.

It also had several bookstores—my go to places in any town. Decades ago I’d made the mistake of bringing Anna Karenina to read while traveling through India. The juxtaposition between place and page was so jarring, I left Anna, alive and well, in Rajasthan. Since then, I try to read books that reflect/enhance my local experience. Knowing nothing of Icelandic literature including their sagas, I inquired about Icelandic “must-reads”. I followed the young salesman as he wandered around the shop and left a short time later with two books in hand, Independent People, by Halldor Laxness, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Heida: A Shepherd at the Edge of the World by Steinunn Sigurgardottir. (Icelandic surnames traditionally take the first name of the father–sometimes mother–and add at the end “son” for sons or “ dottir” for daughters. I’m not sure how this is resolved for the gender-fluid.)

Throughout my wanderings I don’t recall anyone wearing a mask. It seemed to be the land that forgot Covid.

My plans were still unknown, beyond my three nights in Reykjavik, but renting a car was a must. I searched “best car rental in Iceland,” and Lotus Car Rental came up. The accolade was warranted: they offered excellent service, a reasonable arrangement, and tremendous flexibility–a huge plus. I picked up the Lonely Planet Iceland Guide and a roadmap.

The population of Iceland is around 380,000 and a third are residents of Reykjavik. Roads throughout the country are mostly two lanes with no shoulder. Traffic, particularly outside the city, is light. Some tourists have interpreted this to mean that stopping in the middle of the road to take photographs is okay. Watch any Iceland do’s and dont’s videos before heading off. They’ll all tell you, It is not! More tips include: watch out for animals, drive slowly on gravel, check weather conditions regularly, and be cautious crossing rivers, no matter how shallow they appear–best to let someone else cross first. I also learned about F-roads (but not what the F stood for). They require 4×4’s for the challenging terrain, including river crossings. Admittedly, I’d rented a 4×4 for additional driving stability/security on unpaved roads. Not to test my Do Not Panic! skills.

Normally summer is peak tourist season. Weather is wonderful and days are long: sunrise was around 3 a.m. and sunset around 11 p.m. However the number of tourists was drastically reduced. I still hoped to explore the lesser known parts of the country. A rough plan began to formulate. I would drive as much of Iceland’s coast as possible,

beginning with the hand extending northwest of the island known as the Westfjords–the least populated and visited region.

Driving out of Reykjavik toward Arnarstapi I duly concentrated on the winding, narrow road. But glimpses of green fields punctuated with vivid wildflowers against the expansive sky were unavoidable. The image contrasted with the land my critical eyes had initially gazed upon. Beauty emerged. The open windows drew in a breeze but little noise.

Waterfalls were everywhere.

I’d booked a home in Arnarstapi for three nights. The upstairs was reached by steep stairs that looked more like a ladder. The windows afforded splendid views. In addition to some wooden homes, the village consisted of a small hotel, church, and café but they were all closed. There were no shops (I’d stopped at a supermarket en route for the basics), or town center. The only animation came from some sheep. And a bird in the high grass–as I neared it danced about as if it had a hurt wing–a ruse to keep predators away from it’s young.

I wandered down to the tiny port and a café, that looked like it’d been a fishing shack. As I sat on the deck eating a sandwich and watching the sea, some Icelanders gathered.

The adults wore classic woolen sweaters. Kids wore coveralls and knee-high rubber boots. They walked to the water’s edge laughing and playing. Their language entwined with the sea air.

I’d made some effort to learn a few words. Saying hello/ hallo and thanks/ takk fyrir was simple enough, but its complexity spiraled quickly from there.

Icelanders made up the greatest number of tourists I met throughout my trip: the pandemic was a great incentive to explore ones own country. Most spoke English very well.

Hellnar, the next village over was reached by a coastal path.

I followed it through rough black lava fields and rock formations carved by the sea. While enjoying the stunning scenery, artic terns began swooping down to peck at my head. Unknowingly I’d walked into their nesting grounds. Some walkers began swinging sticks over their heads. I was happy to leave the terns as quickly as I could and walk again amid the peace and quiet.

After stopping at more waterfalls, picking up three soaked scouts hitch-hiking, and seeing my first glacier-peaked volcano in the Snaefellsjokull National Park with black sand beaches, I arrived in Stykkisholmur. Its soul is its port. The town’s modern art museum is perched on a hill above it and showcased Roni Horn’s 24 glass columns of water,

a shop displayed the humane process of gathering eider down (considered to be the highest quality in the world) from abandoned nests for its products, and it’s where I had the best fish and chips I’ve ever eaten prepared by teens in an unassuming truck set up in a parking lot; the fishing boats provided the town’s beating heart. And ferries provided passage to Flatey Island.

I bought a ticket to Flatey Island in Stykkisholmur’s ticket office/shop/café and a copy of The Flatey Enigma by Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson. Although I rarely read murder mysteries, I couldn’t resist reading a book that takes place on the very island I was going to (It’s quite different from Independent People– an extraordinary, brilliant book by the way– but the mystery was fun and involved an actual medieval manuscript).

“Flatey” Island aptly means flat. It’s also tiny. The island spans about two kilometers long and about one kilometer wide. The summer population swells with visitors and those staying in their summer homes. The winter population is around five. Accommodations are limited. I’d found a room with shared bath in the sole hotel, Hotel Flatey, for two nights. One car and one tractor passed by on the one road I followed from the dock to the old village. That was pretty much the extent of the traffic.

The hotel had a restaurant, where I had most of my meals—it was the island’s only dining option. My room had a single bed and a sloped ceiling that nearly met the wooden floor. A small window was fit in the space between. It offered a view of the sea. I sat atop a cushion. As I took in the seascape, the sky darkened and wind picked up. A flock of eider ducks with their young showed no hesitation in negotiating the strong gusts and turbulent sea. All of them just bobbed and bobbed some more, while the anchored boats violently tossed and swayed.

The island was splendid and despite its size had everything I needed. Time there had a pace all its own. The sea, wind, birds, and sheep were often the only sounds to interrupt the silence. I wandered along the various paths. Getting lost was not possible. There was always something to notice and admire, including an unexpected and curious totem.

I wandered into the church where the interior is wonderfully decorated and the central character looks like a typical fisherman donning an Icelandic sweater.

I wandered past rams who watched my every move.

And I wandered along the road I’d followed three days before back to the ferry. Returning to Stykkisholmur I picked up my car and continued along the coast.

to be continued…