28 October to 28 November, 2019

Navigating the Setouchi Triennial for the first time was daunting. The twelve islands in the Seto Inland Sea, that host the three season contemporary art event, were unique in size, had names which were difficult to roll off my tongue e.g. Ogijima, Inujima, Naoshima, and visiting all, or at least most of the sites, required planning.

Transportation and housing options varied, and although the Triennial isn´t well known outside of Asia, it still attracts huge crowds and I was hoping to avoid them.

I looked for a convenient base to begin my explorations and was fortunate to find the exceptional Wakabaya Guesthouse in Takamatsu, one of the two port cities that provides access to the islands. I arrived from Kyoto by train on a rainy day. The kind owner, Takeshi, whose youthful face displayed a perpetual smile, had an abundance of knowledge, an untiring desire to share it, and an endless supply of hot tea.

After choosing a lower bunk in a comfortable, spotless room with eight beds, and returning to Takeshi for more advice, I went in search of a recommended restaurant “where only locals go.” A young woman from Shanghai, also staying at the guesthouse, joined me. She was traveling alone for the first time—and loving it. Her English, which she honed by watching Gossip Girls, was flawless.

The small restaurant on a quiet street, run by a spry woman, decades past middle-aged, doing all the cooking and serving, was far from undiscovered—the majority of diners were tourists—but the fresh seafood was delicious.

The Setouchi Triennale began in 2010, and takes place every three years, as an effort to revitalize the region. People had sought opportunities elsewhere, leaving the islands with a decreasing, aged population (the average resident is around eighty), and many homes and schools vacant. Permanent museums were built and international artists were invited to create work throughout the islands, often in the abandoned structures. The event began attracting thousands of visitors.

Takeshi mapped out a strategy, given my luxury of time, to visit the less popular islands and sites during the Triennale and visit the others with star attractions later on. He recommended I begin with Oshima and Isamu Noguchi’s studio and home.

The following morning I walked to a nearby station and took a train to the port. Commuter trains pass through the streets of Takamatsu frequently and the railroad crossing signals quickly became a familiar sound. The car was crowded with men, and a few women, wearing business attire. I stood out in my casual clothes, and as the only foreigner.

I walked to a 7-Eleven to buy some coffee and warm red bean buns, keeping an eye out for the bicyclists riding on the sidewalks. Takeshi had said it was unlikely that I’d find anything to eat on the island so bought some cooked fish, rice, vegetables, and several bottles of green tea for later.

Freshly prepared food-to-go in Japan is practically an art form. 7-Eleven, Lawson, and Family Mart are ubiquitous convenience stores throughout the cities in Japan and offer a wide choice of tasty meals. However, everything was wrapped in plastic, then put in plastic bags, with plastic wrapped utensils, plastic wrapped napkins, and sometimes another plastic bag. Coming from countries where asking for a plastic bag could result in getting a dirty look and a comment like “Plastic is dead, get over it.” the unchecked use of plastic took some getting used to.

The ferry port was already crowded at 9 a.m., but as I had hoped most of the people were there to visit the main attractions of the Triennale: Naoshima and Teshima islands.

Oshima, one of the smallest islands, did not covet the same attention. I took the short ferry ride with a few tourists, and a large group of co-ed students with matching white caps and shirts, black shorts or skirts, white sneakers, different color school bags, violet ties, clipboards, and yellow umbrellas. The teacher never uttered a sound above a whisper, but the teenagers, like a disciplined orchestra, followed the subtle instructions of their maestra, and demonstrated perfect decorum throughout the journey.

I followed the group to a visitor center where a tour was offered, but the guide spoke little English. He led me to a young woman sitting at a table with the Setouchi Triennale flag. Her English was excellent and her enthusiasm was palpable. She sold me the necessary “passport” for the Triennale, offered some suggestions–the forest walk was not to be missed–and gave me a map. She acknowledged that the island did not attract many visitors, but it was her favorite.

I walked to a row of small buildings which housed installations, then took the requisite forest path–it was lush, quiet, beautiful, and dotted with curious ceramic forms and signs with poetic personal accounts of those who had lived there. The history of the island unfolded.

It is not a happy one.

Oshima in 1909 became a leprosy colony. Under a new law people afflicted with the disease were forced to live there, separated from their loved ones. Patients were stripped of their freedom and subjected to hard labor and tragic injustices. The law was repealed in 1996.

Much of the art paid tribute to the suffering these people endured. The tiny, beautiful island seemed incapable of containing all that sorrow.

Some survivors of this era have stayed on with no where else to go. While I strolled along the well-tended paths near the island’s buildings, a curious and grating tune played continuously from a series of loudspeakers. I was reminded of the 1960’s television show The Prisoner. I learned the music was intended to keep the blind residents safe and guide them from straying too far.

The following morning, after buying my breakfast and lunch, a routine already established, I set off to visit Megijima and Ogijima.

At the ferry terminals, cheerful volunteers distributed maps with the numerous art sites marked out. The atmosphere was festive. My “passport” was stamped at each site. Megijima, larger than Ogijima, but still tiny at 2.5 square miles, had bikes to rent. I opted to visit on foot. Wandering through the narrow lanes gave me a sense of time past.

Picturesque abandoned wooden homes were transformed by the art and infused with life. Sites were unique and captivating. Ogijima’s charming new café/library was an effort to cater to and potentially attract more residents.

Despite taking the first ferry in the morning and returning on the last ferry in the early evening, the hours weren’t enough to explore the islands. I wanted to stay somewhere, but the few accommodations I’d found were either closed or full.

That evening, sitting comfortably at a low table in the guesthouse, sipping a cup of tea, I asked Takeshi for advice. He opened a thick folder filled with names, phone numbers, maps, ferry schedules, and assorted information. After looking through it and asking me some questions he made a phone call that went on for some time. Even though he was speaking Japanese I could tell he tried to bring the call to an end several times. Finally he hung up, told me I could stay a few nights on the small island of Awashima, and added, “The owner likes to talk.” His smile turned wry.

The road from the ferry dock to the Awashima Lodge was steep, curved, and followed the coast. A passing car was an anomaly. As I trudged along, following the map Takeshi had drawn for me, glad I’d left most of my things at his guesthouse, I gazed out at the sea. The lodge was a simple, large, two-story rectangular building a short walk from the main road.

The owner, an elderly man, greeted me upon arrival and brought me to his and his wife’s living area on the ground floor. It was crammed with chairs, tables, boxes, and other things. After a quick introduction, he only spoke Japanese and my vocabulary remained quite limited, I was shown upstairs to a long corridor. A tiny toilet was down the hall, the shower was downstairs.

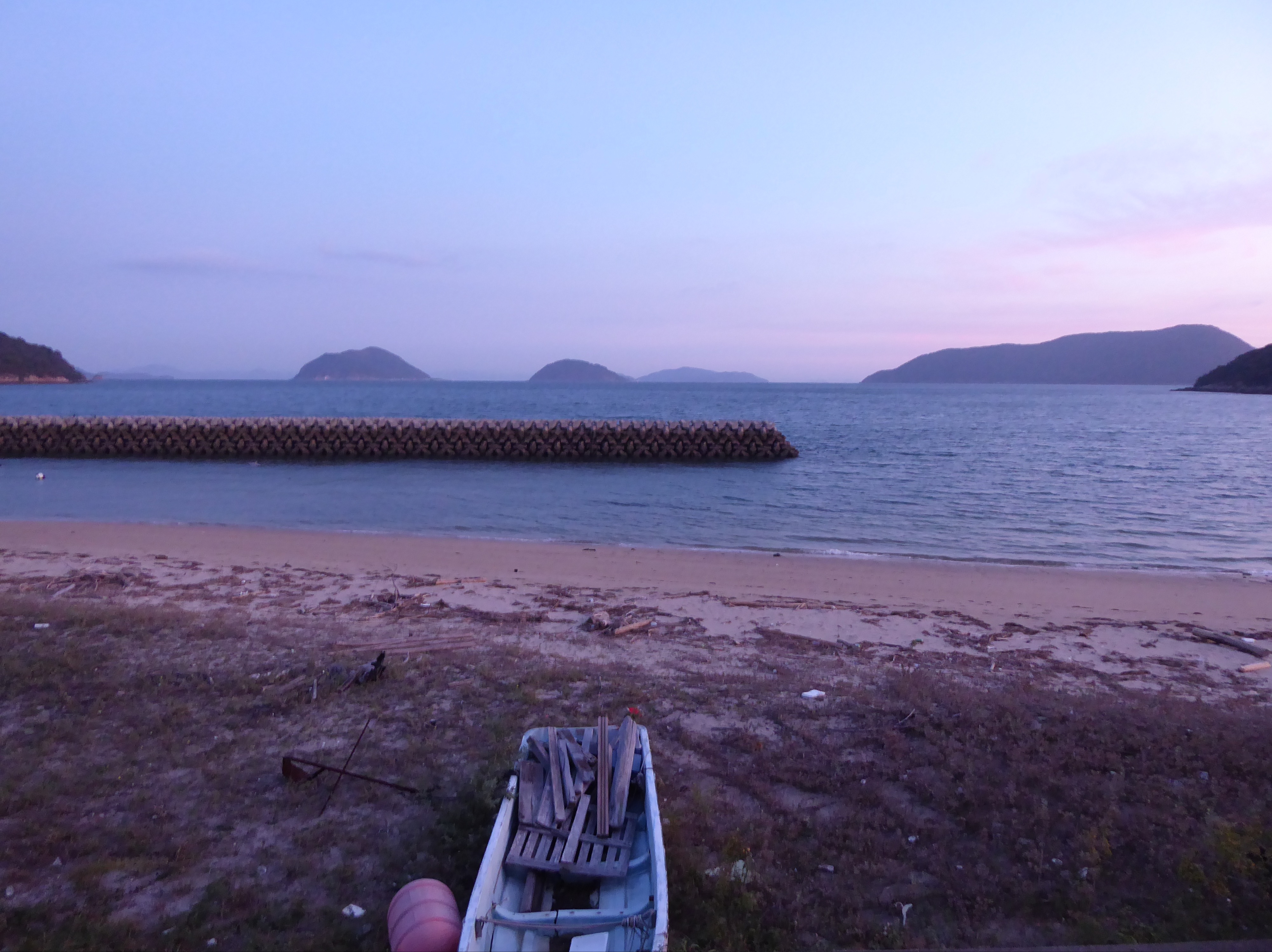

My room had a sink, a narrow futon with some blankets, a small pillow, tatami mats, and a bare bulb hanging from the ceiling. There were no decorations except for a faded calendar hanging from a hook, however windows filled the far wall. I walked across the room and looked out to a small beach, the sky, the sea, and the islands. The only sounds came from the wave’s gentle rise and fall. I needed nothing more.

Later that afternoon I met the wife. She began speaking to me in an endless burst of sound. Despite my best efforts to demonstrate that I did not understand what she was saying, she just kept on speaking. I tried using Google translate, but it was an abject failure. I spoke, then showed her the screen with the words I said now in Japanese, she looked at it and wouldn’t utter a word. As soon as I put the phone down she began speaking again. I tried using hand gestures in the hopes she would do the same, offering me some clues, but she spoke with her arms stubbornly at her side. Fortunately another guest arrived. Sakiya, a lovely young woman from Osaka, spoke some English and offered to translate. She listened to the wife at length and asked “Is dinner at six okay?”

Awashima offered no dining opportunities so breakfast and dinner were included in the price of lodging. A few minutes before 6pm, after removing my shoes at the front door, putting on the downstairs slippers, different from the upstairs and bathroom slippers, then removing them to enter the tatami dining area, I sat on a cushion in front of a place setting at a large low table. Sakiya and Ryo, another guest, a sound engineer from Kobe, were already seated. Several courses of vegetables, sashimi, smoked fish, and fruit were served soon after with hot tea. It was a delicious meal, and served by the husband with pride. Everything was fresh and came from the area.

The wife’s bad knees made the ascending and descending of the high step to the room difficult leaving her free to take a semi-reclining pose and talk non-stop throughout the meal. I tried to be polite and look like I was listening, but when it seemed as if she was never going to run out of air, I excused myself to the quiet of my room upstairs.

Sakiya came by later that evening and asked if I wanted to come outside to look for sea fireflies. I’ve always loved fireflies, but I’d never heard of sea fireflies. I quickly followed her downstairs. Sakiya, Ryo, the husband, and I walked in silence to the water’s edge. The husband was as reserved as his wife was long-winded.

Donning high white rubber boots the husband started stomping by the shore. The enigmatic creatures reacted to the movement. Specks of blue light suddenly appeared and offset the darkness. The sea fireflies’ eerie glow complemented the stars. We began stomping our feet too, wanting more. The show continued until the chill of the air drew us reluctantly back indoors.

The following morning, while standing on the beach. Ryo recorded Sakiya and me reciting words respectively in Japanese and English. I spontaneously chose sky, air, waves, sun, moon, and sea fireflies/umi-hotaru. It was a way of saying goodbye. They were heading back to their homes and took the first ferry from the island. I decided to stay two more nights and spent the days exploring Awashima, Takamijima, and Honjima.

If I did see the residents, which was not common (I generally encountered tourists or volunteers), they were mostly tending to their gardens or fishing nets, working with the fishing boats, hanging up their laundry, carrying a parcel, or quietly taking a stroll. Life during the Triennale didn’t seem to alter their routines.

They were predominantly women and all of advanced age. I was struck by their indifference to the tourists and the potential for economic gain. In addition to a lack of places to stay, food and drinks were rarely sold, shop hours were short and erratic, and there was nary a souvenir for sale. But the residents were not unfriendly. I shared a lovely moment with a woman as she weeded her garden. She seemed pleased to have the company and I was delighted to understand the word “broccoli” as she spoke.

I returned to Takamatsu for some days of rest and further exploration. I wandered the city’s center of long covered arcades that went on for blocks, packed with shops and restaurants.

And took a train to the mountain/park Yashima where I hiked to the top for a splendid view and visited the impressively designed Shikoku Mura open air museum and gallery. Ancient homes and buildings from the region had been relocated to a strikingly beautiful, lush environment offering visitors a chance to stroll through history and learn about the past. The modern gallery on the same grounds offered a stark but stunning contrast.

With the Triennale officially over, it was time to visit the popular islands, hopefully without the crowds. I managed to find a place to stay on Teshima for four days in the welcoming home of Kureishi. He had been born and raised on the island, left for many years to see the world, returned, and opened his family home to guests. I spent the days exploring the charming island on foot and bicycle, and sharing time with Kureishi and a new found friend, Chika, who is Japanese, but lived in Sweden for many years.

I met Chika working at the Yokoo house, a museum designed by architect Yuko Nagayama, in collaboration with artist Tadanori Yokoo, to showcase the latter’s artwork. It was converted from three traditional homes, redesigned with rooms and garden of various shapes, colors, and forms: reflective red Plexiglas walls lined the entry, koi swam beneath the transparent floor, paintings, some lit from within, hung on the walls, and a faux silo’s interior was completely covered in old postcards. For each step my concept of a “museum” was stretched.

But the Teshima Museum shattered it.

Getting inside the Teshima Museum requires a timed ticket and during the Triennale, reservations were made months in advance. But as hoped, the crowds had left and I was able to get a ticket easily.

I’d rented an electric bike for my stay and was happy to get some assistance on the long steep hills to get there. I parked in the area specifically for bicycles, a popular way of getting around the island, and entered a small building used for welcoming guests and checking-in. The staff directed me to a path that led around the hill, through a small wood, and a bench to stop and enjoy the view, then continued. It was a pleasant walk that took a few minutes. During the Triennale with the long lines it would take much longer, and was probably designed to please as well as placate impatient visitors.

I arrived at a sign and waited, a young woman wearing white and holding a walkie-talkie appeared. She asked me to remove my shoes, place them on a low rack, and to please remain silent. I entered a huge, rounded, cement space with a single entry, like one for a large igloo.

Once inside I tried to take in the extraordinary surroundings. The curved walls, also cement and completely bare, met the floor at a sharp angle. The only light came from the entry and two large, oval openings of different size, spaced a considerable distance apart. The openings let in the elements and offered views of the sky. While orienting myself, an attendant demonstrated that I watch my step. Tiny rivulets of water randomly appeared and traveled along the slanted floor. I began walking around and noticed a small piece of porcelain, there would be more.

Fearing I might break something, my pace slowed. Each step became conscious. I watched the droplets of water emerge and noticed the subtle changes in the light. I listened to the near silence and looked around at the other visitors. One woman sketched. Some chose to sit or lie on the floor with eyes closed. All was calm.

And then some people began speaking and the acoustics of the structure amplified their voices to a near roar. They were oblivious. I was annoyed. Then John Cage’s composition 4’33”(four minutes and thirty-three seconds) came to mind. It is a piece Cage composed for musicians to have, but not play their instruments for the duration. He intended the ambient sounds to provide the “music.” This helped, but I was pleased when the quiet was restored and lingered.

I had the good fortune of returning twice more. I specifically chose different hours of the day and was rewarded with the contrasting light I had hoped for. One day it rained and the raindrops mingled with the drops emerging from the floor. Reflective puddles were formed. Another day the wind picked up and leaves floated in creating swirling patterns in the air. All was in flux.

On the island of Inujima is a museum converted from a copper refinery. It uses solar, geothermal, and other natural energies, and was designed to minimize environmental impact. As I wandered, hesitantly, down pitch black hallways suddenly encountering visions of the sun, and saw the deconstructed home of Yukio Mishima swaying in the wind my imagination was continuously challenged and my senses were energized. While strolling around the stunning island I discovered quiet village life, the utopian Life Garden project, and fish leaping high from the sea.

Naoshima, the most famous island, has the immensely popular Chichu Museum among other wonderful museums and sites. There was much to enjoy.

Shodoshima’s autumn colors were peaking. Like the other islands it had an abundance of natural beauty, intriguing and impressive art, picturesque hamlets with narrow lanes, and women wearing large bonnets tending their fields, but also a Greek windmill, and a park of roaming Macaque monkeys who visit for feedings.

One day, just before a storm, I found a small café serving lunch and waited until the clouds cleared. Time passed peacefully there.

I’d rented a lovely home for two weeks on the mainland, just outside of Uno, across the sea from Takamatsu. It was an ideal location to explore many of the places I’ve mentioned, catch my breath, visit another onsen, and Kurashiki a picturesque, but touristy town, return to Teshima for a final picnic with Chika, and plan my next destination.

The temperature was dropping, I wasn’t quite ready for the cold, and sought out warmer climes.

I booked a flight to Okinawa.

to be continued…