My time in Madrid, although worthwhile, has not been socially satisfying. And I’ve missed the succor of nature. So when the owners, J&A, of my temporary home here, invited me to Extremadura for “vendimia (grape harvest)” I readily accepted. I didn’t know what to expect and only thought to ask “What clothes might be best?” “Clothes for the country.” was the response.

I briefly met J&A when I arrived at their apartment in Madrid and liked them immediately. I hadn’t seen them since.

I did ask my Spanish teacher, who came from Extremadura (the heart of old Spain as my guide book suggests), what one actually does at a vendimia. He said it was a great excuse for people to eat, drink, and party. (He’s twenty-eight years old.) I asked if there was work to do. His answer was an emphatic “No.”

I left Madrid by bus on Friday at 3:30pm and arrived in Trujillo nearly 7pm with the sun still high in the sky. J&A warmly greeted me at the station. We then drove twenty minutes to a quiet, small town which we quickly passed through, although we were not traveling fast, and soon came to a narrow, steep, dirt road which led up to their renovated stone “ruin.”

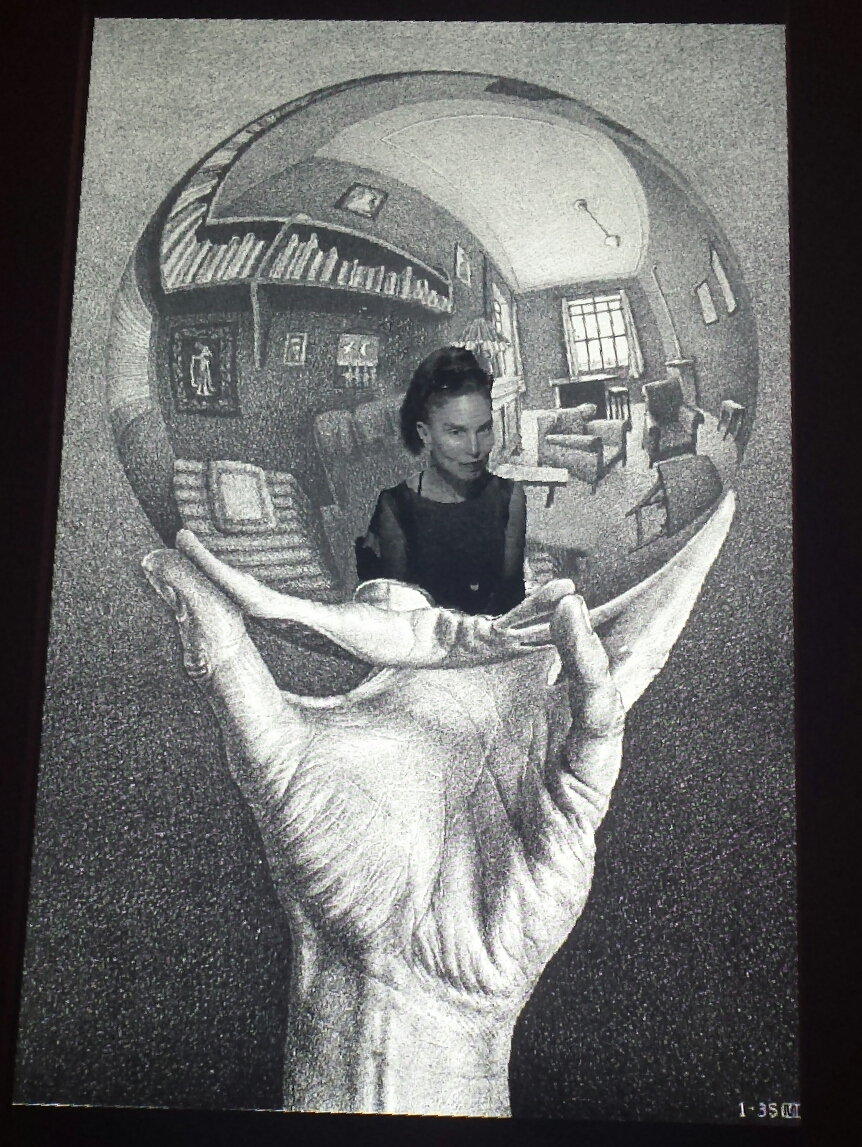

Their home had been constructed two-hundred years ago for workers to store harvested grapes and produce wine. Huge earthen vase-like containers still stood as proof. One room had a slanted cement floor and hole for drainage either for water or wine I do not recall. Another had a massive cement tub which drained off into a small pool. Yet the structure with high ceilings, exposed wooden beams, and fireplaces, now painstakingly converted into a home with eclectic furniture, art, and an endless array of books, exuded comfort and warmth. The home offered J&A, their many cats, and fortunate guests a place of tranquility and beauty. Their land extended for acres with olive trees, fig trees, almond trees, and an abundance of plants.

J&A had also invited for the weekend a Spanish/Argentinian couple who arrived late that evening with their children: a charming seven year-old girl and a two and one-half year old bruiser who made his desires clear with loud monosyllabic commands.

J&A said the vendimia would begin at 7:30am the following morning. At 1:30am I wished everyone goodnight. I slept soundly and at 7am I went to the kitchen. It was empty and I heard no one stirring. J. came in a short time later, alone, to prepare coffee and breakfast for us. Everyone else, having gone to bed at 3:30am remained sleeping.

J and I walked a short distance to the British neighbors John and C.’s vineyard/orchard where the vendimia would take place. They had invited their four British friends too.(My hope of practicing Spanish all weekend was quickly dashed.). The eight of us were soon equipped with gloves, small shears, and wide-rimmed straw hats. It was now apparent that the celebrating would have to wait. We were there to harvest grapes. J had lent me a pair of canvas shoes and cotton pants. I had brought only sandals and summer dresses for “the country festivities.”

John explained that two hail storms had done extensive damage to the vineyard, but grapes were still abundant. The bushes grew helter-skelter up a hillside and stretched over a fair distance. Our task -the harvesters- was to first remove the protective green nets around each grape-bush (they were grounded with stones), cut off bunches of grapes, remove any bright green, bitter or overly damaged grapes then place the dark red ones into a large plastic bucket we had each been allotted. We worked alone. Wrestling the net from the bush was time-consuming and gleaning the desired from the undesired grapes was slow going for my untrained eyes and hands. But it was pleasant to be in the fresh air amongst nature engaging in an ancient task. Buckets were eventually filled and John driving a tractor, collected, emptied, and returned them (I thought of Huck Finn and his scheme to paint a fence by enticing others with the notion of fun.). Hours went by. As the sun rose and with it the temperature, my sun hat could only do so much to keep me shaded and cool. The task became arduous.

I eventually took a rest inside John and C’s cool stone home. I thirstily drank a glass of water and chatted with C. while she prepared snacks and drink. Most of us took breaks while some toiled on outside non-stop. I thought of slaves and migrant workers who have toiled in fields for centuries without the option to rest when they were weary or slack their thirst.

Afterwards I returned outdoors, this time with a different task. I was to pick figs for a tart. Despite the eighty fig trees on their land the pickings were slim. Passerbys and birds had gotten there first. I managed to cover the bottom of a handbasket.

By two pm the vendimia was done for the day. We were then gathered to press the grapes. Our jobs were divided into several tasks. Mine, along with two other women, was to take the buckets of grapes after pressing and based on John’s orders dump the contents again into the pressing machine “arriba (up)” or walk a few strides to a shed and, pour the sufficiently pressed grapes into large metal vats “dentro (inside)”. The team work of all involved went smoothly and a camaraderie was ever-present. The seven year old girl-the only one of her family to participate in the chores-had her feet washed, then happily and enthusiastically stomped on a basketful of grapes keeping the tradition alive.

When the grape-filled sacks of our labor were all pressed, we hosed off the tools, machines and ourselves. We then all sat at a large outdoor table toasting, with last year’s vintage, to our accomplishments and dining on lamb, shrimp, salads, fresh vegetables, cheese, quiche, and fig tart.

The evening cooled, conversation and wine flowed.

I volunteered to join them in the same tasks the following day.

The harvest despite the hail had been successful. Now John would be tending to the production of wine on his own for the next several months.

My invitation to stay at J&A’s kept on extending, but by Tuesday evening I reluctantly took the bus back to Madrid.

I left Extremadura with memories of the vendimia, and my time to relax and read, enjoy the company of others, blanch almonds and peel grapes for a traditional cold soup, pick raspberries, beets and herbs-all from the local land, watch a full moon rise, and gaze at the constellations of a country sky.